Rene Smith shared their story and experiences with us recently and you can find our conversation below.

Good morning Rene, we’re so happy to have you here with us and we’d love to explore your story and how you think about life and legacy and so much more. So let’s start with a question we often ask: What is a normal day like for you right now?

Most mornings I wake up in a pile—Lady the Corso, Bella the Pitbull, Dobby the Chihuahua mix, sometimes a kid (or two), all stacked on top of me like a living blanket. I let the early dogs out while quietly dodging child interaction just long enough for my brain to boot up. Then comes Kodi, my shepherd, who I lovingly call “Psycho” because his kennel bark could shake drywall. Shepherd folks get it.

Once the first crew is back in, it’s food, meds, kids, fish. Then Louie gets his solo rotation—he doesn’t share space well with other dogs, so he gets the morning slot with us humans. After that, Charlie the Pittie and Lilly the Rottie get their sunbathing time before the Texas heat turns the yard into lava.

If I can physically manage it, I walk to the tree at the edge of the property—one dog per day, seven days a week. It’s part ritual, part reset. The work gets built around the life, not the other way around. That’s been a shift for me: recognizing that I have a full life, and letting that be the foundation—not something I squeeze work into around the edges.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

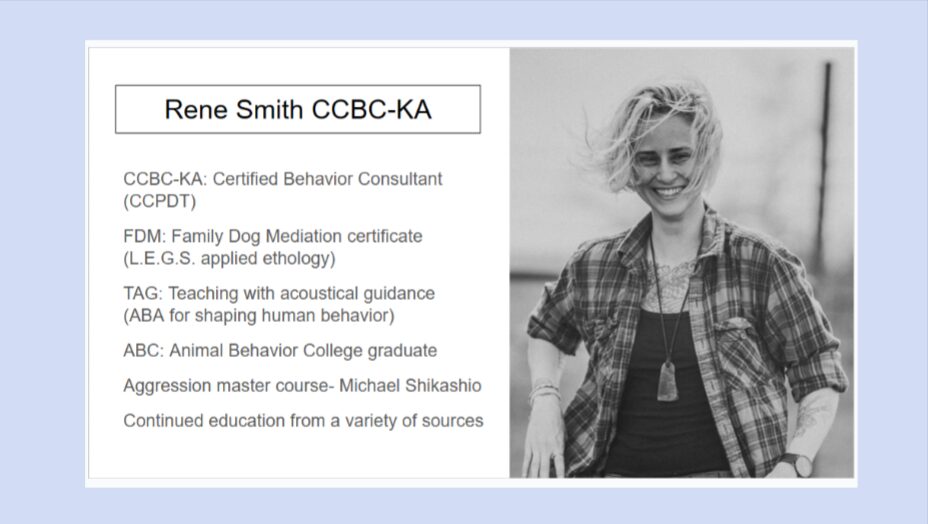

I’m Rene, Certified Canine Behavior Consultant and founder of Street Dog Rehab. I was originally on track to become a service dog trainer, until a multi-dog pack fight erupted in my own living room. That moment threw me straight into the deep end of behavior work, and within a year, I earned my CCBC-KA certification and shifted course entirely. Since then, I’ve been building systems for human learners navigating complex, emotionally charged cases—and I’ve never looked back.

For years, I worked in person. When the pandemic hit, I pivoted to virtual training. At first it was a stopgap. Now, it’s my specialty. I’ve had two surgeries and a seizure in the last four years, and the flexibility of virtual coaching has let me continue supporting families across the country through all of it. But it’s not just about accessibility—it’s a different skill set. Virtual work demands sharper language, clearer scaffolding, and an ability to translate behavior patterns across screens. I’ve spent years refining that, so my clients get more than just information—they get systems that work in real life.

Street Dog Rehab isn’t about fixing dogs. It’s about creating momentum—for learners who are overwhelmed, for dogs who’ve been through the ringer, and for relationships that need more than just cues and treats. I work with families navigating aggression, trauma, and unpredictability. My goal isn’t perfection—it’s progress people can actually feel and training strategies that just make sense.

Appreciate your sharing that. Let’s talk about your life, growing up and some of topics and learnings around that. What part of you has served its purpose and must now be released?

I’m phasing out my “everything’s a crisis” default operating system. Not because it didn’t work—it worked extremely well. When behavior cases felt like bomb defusal, I ran tight protocols and delivered outcomes under pressure. My brain is brilliant at narrowing focus especially when safety was on the line. That part kept me and my clients safe.

But now, it’s not my default setting. These days, I flag the context first. If we’re in containment mode, those skills kick in fast. But if we’re not, I start from a different place—one that leaves room for nuance, creativity, and actual problem-solving. The crisis brain hasn’t disappeared. It’s just been rerouted into contingency planning, not the starting place.

It’s still the same skill set. I just use it differently now—and it’s nice not treating every session like I’m the last dog trainer on Earth.

When did you last change your mind about something important?

I used to think the structure itself was the point — that if I built the right system and filled it with enough effort, it would earn trust and support. Over time (and through many mistakes), I realized a system is only helpful if it’s actually helpful. The container is just a tool; the value is in what it holds. If a framework stops working for the people it’s meant to serve, I change it. Sometimes that means small tweaks, sometimes a full rebuild.

Now I treat every structure as temporary. Some last years, others only a few weeks. When something starts creating friction instead of momentum, I adjust it or scrap it. That shift has made my work lighter to carry and easier to adapt, without losing the core of what matters.

Next, maybe we can discuss some of your foundational philosophies and views? Where are smart people getting it totally wrong today?

I want to start by naming what’s already being done well. Smart, thoughtful trainers and owners are leaning into research and choosing positive reinforcement because it’s the most humane, low‑risk path. That’s the right call.

Where it can go wrong is when we try to run a protocol before the dog has the basics in place—like being able to regulate their arousal or feeling safe enough to offer new behaviors under stress. Without those, even the best plan can stall.

So we start by looking at the dog’s capacity in that moment. If they’re too stressed to take food, we don’t push treats—we make the environment predictable so they can settle. We test starting points in low‑risk ways, so even if it doesn’t “work” right away, it still tells us something useful about what they’re ready for.

The method isn’t the problem. The assumption that the learner is ready is. The only way to know is to try, watch, and build from what the dog actually offers.

Okay, so before we go, let’s tackle one more area. How do you know when you’re out of your depth?

I can tell I’m at my limit when the case starts swallowing everything else — my notes get thin, follow‑ups slip, and I can’t stay regulated long enough to write a clear protocol. If I can’t name the learner’s entry point or sum the case up in a few lines, that’s my red flag.

Early on, I ignored those signs. I thought taking the hardest cases proved I was good at this. Sometimes it did — but it also meant I was in over my head, and that wasn’t helping anyone.

Now, when those flags pop up, I pause. I ask questions. I call in support. I’ve learned that catching the mismatch early isn’t failure — it’s data. And the difference between being out of depth and working at my growth edge is usually just the willingness to ask, “What am I missing?”

Contact Info:

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/streetdogrehab/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/rene.smith.925088

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@reneshumans